(Translated from Swedish by Google Translate)

The Manilla School, or as it was called before, the General Institute for the Blind and Deaf-Mute, is Sweden's first school for deaf children and young people.

The school was founded in 1809 and from the beginning had students who were deaf or blind, and sometimes also mentally retarded. The man who founded the school was called Pär Aron Borg and was a real firebrand who was highly valued by his students.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Borg had for a few years taught students on a private basis, at home in his own apartment. The very first student was Charlotte Seyerling who was blind. The knowledge that Pär Aron Borg's students acquired, and which was proven through public examinations, meant that the school received an annual state grant in 1809 under the patronage of Queen Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta. Thus, Sweden had its very first deaf and blind school.

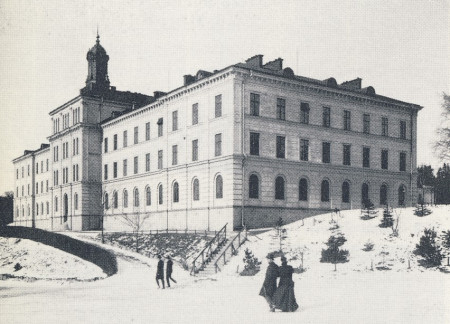

The move to Djurgården

In the first years, the school was located on Drottninggatan in Stockholm. In 1812, the business was moved to Djurgården, where it is still conducted today. To begin with, students and teachers lived in the building that had already existed in the area, Öfre Manilla. It was a Spanish envoy who previously owned the land, had given the area its name to pay homage to his country that colonized the Philippines, with Manila as its capital. The houses in Upper Manila were equipped so that they would be suitable for school teaching and housing, both for students and teachers. The school was thus a boarding school. At the same time as the refurbishment, stables and a forge were also built, among other things.

During Pär Aron Borg's time, students were taught using the hand alphabet and sign language. As there was still no proven teaching method in Sweden, Pär Aron himself constructed the Swedish hand alphabet and sign language. The hand alphabet is still used today.

The students were mainly taught religion and crafts. The religion helped the students reach confirmation, something that was considered very important in the society of the time. The craft skills would help the students to provide for themselves after the end of school. Other theoretical subjects were language, reading and arithmetic. During Pär Aron Borg's time, geography, astronomy and natural sciences were later added.

Who got to go to Manila School?

At the institute there were both paying students and free students. The free pupils consisted partly of pupils admitted at the expense of the royal house or from the school's fund, and partly of such children as were selected by the boards of their diocese. During the school's first year, the students' age at admission had varied between 6 and 36 years. In 1816, it was decided that the admission age would be 8-14 years, but despite this, over-age students were admitted for a long time to come.

To begin with, no fixed apprenticeship period existed. The students remained at the school between one and ten years, and in exceptional cases even longer, depending on aptitude and development. Most, however, spent between seven and eight years of their lives at school.

(..)

The school's development under Ossian Borg

Manilla's founder Pär Aron Borg remained headmaster of the school until his death in 1839. This year he was succeeded by his son Ossian Borg. Unlike his father, Ossian believed that students must be educated in mainly theoretical subjects instead of the artisanal ones. Practical teaching had to step aside in favour of the intellectual. However, craft training was still part of the school's activities for a long time.

Spoken Swedish and reading

During Ossian Borg's time as headmaster, Manilla School switched from sign language to oralism, that is speaking and reading, as the language of instruction. This took place in the 1860s. At about the same time, in 1874, a two-year seminar for teachers of the deaf was established at the school, which remained until 1967, when it was moved to the Teachers College in Stockholm.

(..)

Sign language again after more than 100 years

Teaching based on speaking and reading dominated the school's activities until the mid-1970s. For a long time it was considered important that the students became as "hearing" as possible. Through research that showed that sign language is its own language, completely separate from Swedish, with its own grammar, syntax and structure, as well as through the influence of deaf and parent organizations, the view on teaching slowly changed.

Manillaskolan now:

Source:

https://archive.ph/2013.08.15-130154/http://www.spsm.se/Vi-erbjuder/Undervisning-i-specialskolor/Vara-skolor/Manillaskolan/Om-Manillaskolan/Skolans-historia/

See all from: